3 Explosive Nuclear Clocks Unveiling Amazing Precision

On This Page

Time, a fundamental dimension of our existence, is measured with increasingly breathtaking precision. For decades, atomic clocks have been the gold standard, leveraging the exquisitely stable oscillations of electrons within atoms. These marvels of engineering, currently accurate to within one second every 300 million years, underpin everything from GPS navigation to global financial transactions. However, the relentless march of scientific discovery demands even greater accuracy. Enter the revolutionary concept of nuclear clocks – devices so precise they could redefine our understanding of the universe. This post delves into three brilliant breakthroughs that are making these ultra-precise timekeepers a tangible reality.

Beyond Electron Transitions – The Core Idea of Nuclear Clocks

Current atomic clocks operate by measuring the energy transitions of electrons orbiting an atom’s nucleus. While incredibly stable, these electron transitions are still susceptible to external electromagnetic fields and temperature fluctuations. Think of it like a delicate pendulum easily swayed by its environment. The solution for a new level of precision lies deeper, literally, within the atomic nucleus itself. Here, protons and neutrons engage in their own set of quantum energy transitions, often billions of times higher in energy than electron transitions. However, there’s a unique exception, a “sweet spot” that scientists have been chasing for decades: the Thorium-229 isomer.

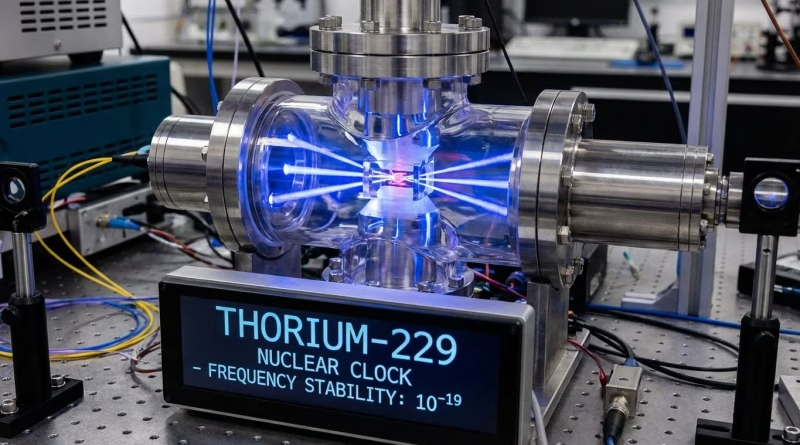

The core concept behind nuclear clocks is to exploit these incredibly stable nuclear transitions, which are intrinsically shielded from external perturbations by the electron cloud and the sheer density of the nucleus itself. The theoretical Q-factor (a measure of clock quality) for a Thorium-229 clock could exceed 10^20, a full two orders of magnitude higher than the best optical atomic clocks today. This translates to potential stability improvements on the order of 10^-19 or even 10^-20, far surpassing the current 10^-18 achieved by leading optical clocks. This leap in precision isn’t just incremental; it represents a fundamental shift in metrology, promising to unlock new scientific frontiers.

The Thorium-229 Isomer – A Quantum Leap for Nuclear Clocks

The quest for a nuclear clock has long been hindered by the extreme energy scales of typical nuclear transitions, requiring gamma-ray lasers that are far beyond current technology. However, the Thorium-229 nucleus harbors a unique isomer (Th-229m) with an exceptionally low-energy transition, estimated to be around 8.2 electron volts (eV). This is comparable to the energy of ultraviolet light, making it accessible to manipulation with cutting-edge laser technology – a critical breakthrough for nuclear clocks. This incredibly narrow transition linewidth implies an astounding potential for stability, theoretically allowing for timekeeping with a fractional frequency uncertainty better than 10^-19.

For nearly 70 years, the precise energy of this transition remained elusive, presenting a formidable experimental challenge. However, a significant turning point occurred with the direct observation of this transition. In 2023, independent research groups successfully detected the gamma-ray emission from the Th-229m isomer. Notably, researchers from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München and the Vienna University of Technology, among others, demonstrated key steps towards isolating and characterizing this state. This monumental achievement, reported in leading scientific journals like Nature, moved the Thorium-229 nuclear clock from theoretical possibility to experimental reality, providing the concrete data needed to engineer these ultra-precise nuclear clocks. This direct evidence validates the long-held hypothesis and paves the way for the next phase of development: clock construction.

Trapped Ions and Optical Lattices Engineering – Extreme Stability for Nuclear Clocks

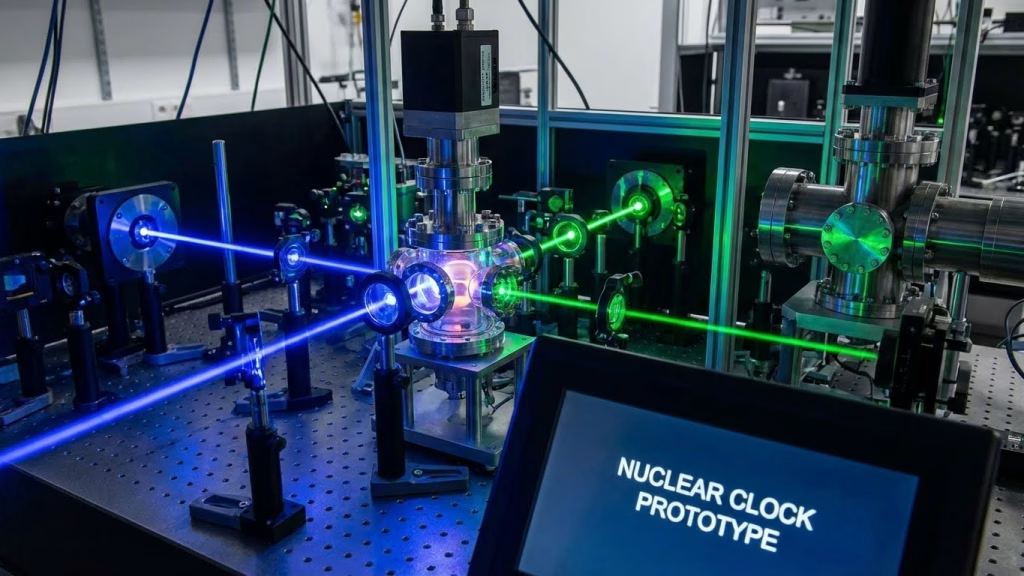

Building a clock based on a single nuclear transition, no matter how stable, requires sophisticated experimental platforms that can isolate and interrogate individual atoms or ensembles with extreme precision. This is where breakthroughs in trapped ion technology and optical lattices become crucial for the realization of nuclear clocks. Ion trapping, a technique pioneered in quantum computing and atomic clock research, allows for a single Thorium ion (or a small chain of ions) to be suspended in a vacuum using electromagnetic fields, completely isolated from environmental noise. This isolation is paramount for maintaining the coherence of the nuclear transition over long periods.

Complementary to ion trapping are optical lattices, which use highly stable laser fields to create a “crystal of light” capable of holding thousands of neutral atoms in a perfectly ordered array. While Thorium ions might initially be trapped individually, the lessons learned from optical lattice clocks – which achieve stability by averaging over a large ensemble of atoms – are directly applicable. By meticulously controlling the environment and interrogating the nuclear transition with ultra-stable lasers, scientists aim to minimize systematic uncertainties to unprecedented levels. Researchers at NIST and JILA have recently demonstrated optical clock accuracy approaching 10^-18, setting a high bar that nuclear clocks aim to surpass by orders of magnitude through these advanced trapping and interrogation techniques. The combination of these technologies represents a convergence of quantum physics and precision engineering, creating the necessary conditions to harness the nuclear transition’s ultimate stability.

Applications Beyond Our Wildest Dreams – Precision Powered by Nuclear Clocks

The implications of having a timekeeping device several orders of magnitude more precise than current atomic clocks are profound and far-reaching, impacting virtually every field reliant on precision timing. Consider GPS: current systems rely on atomic clocks accurate to about one nanosecond; nuclear clocks could push this to picoseconds or femtoseconds, enabling sub-millimeter positioning accuracy globally. This wouldn’t just improve navigation; it would revolutionize autonomous vehicles, geological surveying, and even earthquake prediction by detecting minute crustal movements with unparalleled precision.

In fundamental physics, these ultra-precise nuclear clocks would serve as unparalleled laboratories. They could enable more stringent tests of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, potentially detecting gravitational wave backgrounds or probing variations in fundamental constants of nature, such as the fine-structure constant. Imagine detecting gravitational potential changes equivalent to a single millimeter of elevation across thousands of kilometers – this is the precision nuclear clocks promise, offering new insights into relativistic geodesy. Furthermore, they could act as ultra-sensitive dark matter detectors, searching for subtle interactions that manifest as tiny shifts in the clock’s frequency. For quantum computing and secure communication, synchronized networks of nuclear clocks could provide the backbone for robust, ultra-fast data transfer and processing, paving the way for truly global quantum internet infrastructure. This next generation of timekeeping promises to not only refine existing technologies but also enable entirely new scientific explorations.

The Road Ahead – Scaling and Standardization of Nuclear Clocks

While the initial breakthroughs have laid a robust foundation for nuclear clocks, the journey from laboratory marvel to widespread practical application is still underway. One of the primary challenges lies in scaling down the complex, cryogenically-cooled laboratory setups into more compact, robust, and accessible instruments. Current optical atomic clocks, while incredibly precise, often fill entire rooms; nuclear clocks will face similar hurdles in miniaturization and environmental hardening. Furthermore, the specialized lasers and control systems required are incredibly expensive and demand highly skilled operators, limiting initial deployment.

Standardization will also be crucial. Just as international atomic time (TAI) relies on a network of atomic clocks worldwide, a future nuclear time scale would necessitate global collaboration and agreement on measurement protocols and interoperability. Establishing a common reference for such extreme precision will require overcoming significant technical and logistical hurdles. However, the scientific community is well-versed in these challenges, having successfully navigated similar transitions with previous generations of timekeeping. Early prototypes of simpler nuclear clock components might emerge within the next decade, with fully operational, commercially viable systems likely several decades away. The investment, both intellectual and financial, will be substantial, but the payoff – a new era of ultra-precision – promises to be truly revolutionary. The potential impact on science, technology, and our understanding of time itself makes this a pursuit of paramount importance.